This is the first in a series of posts on the six-session Software in Astronomy Symposium held on Wednesday and Thursday, April 3-4 at the 2018 EWASS/NAM meeting. Each of the six sessions focused on a different aspect of research software,  covering not only specific software packages, but also computational techniques used in data mining and machine learning, open services, software development training and techniques, and getting credit and citations for computational methods. Several sessions included a free-form period in which participants could ask questions, discuss issues, and share information. The last session of the Symposium was a lively moderated discussion among attendees with particular interest in software publishing.

covering not only specific software packages, but also computational techniques used in data mining and machine learning, open services, software development training and techniques, and getting credit and citations for computational methods. Several sessions included a free-form period in which participants could ask questions, discuss issues, and share information. The last session of the Symposium was a lively moderated discussion among attendees with particular interest in software publishing.

BLOCK 1: Software engineering and sustainability, education for better software, & the ecosystem around Python in astronomy

The first session set the stage for the Symposium, featuring a variety of topics of importance when discussing astronomy research software. Alice Allen (ASCL, US) moderated the session. In the inaugural talk, Software Engineers as Partners in Astronomy Software Development, John Wenskovitch (Virginia Tech, US) opened his presentation with a quote by computer scientist and professor Carole Goble, stating that software is “the most prevalent of all the instruments used in modern science.” This was reiterated by others throughout the symposium. Wenskovitch provided statistics on software use and development activities by academics, among these that 92% of academics use software and 38% spend at least 20% of their time developing software. Research software engineers (RSE) provide guidance to researchers on software engineering and encourage the use of tools that can save academics time and effort in their development efforts. Wenskovitch suggests identifying and using the strengths of each, with the researcher bringing domain knowledge and expertise on the research itself, and the RSE bringing development experien

The first session set the stage for the Symposium, featuring a variety of topics of importance when discussing astronomy research software. Alice Allen (ASCL, US) moderated the session. In the inaugural talk, Software Engineers as Partners in Astronomy Software Development, John Wenskovitch (Virginia Tech, US) opened his presentation with a quote by computer scientist and professor Carole Goble, stating that software is “the most prevalent of all the instruments used in modern science.” This was reiterated by others throughout the symposium. Wenskovitch provided statistics on software use and development activities by academics, among these that 92% of academics use software and 38% spend at least 20% of their time developing software. Research software engineers (RSE) provide guidance to researchers on software engineering and encourage the use of tools that can save academics time and effort in their development efforts. Wenskovitch suggests identifying and using the strengths of each, with the researcher bringing domain knowledge and expertise on the research itself, and the RSE bringing development experien ce and software engineering expertise. He provided suggestions for ensuring a fruitful partnership; these include using version control, scheduling time for regular and frequent communication, having a prioritized feature list, testing the code thoroughly using unit, regression, and usability tests, and documenting everything.

ce and software engineering expertise. He provided suggestions for ensuring a fruitful partnership; these include using version control, scheduling time for regular and frequent communication, having a prioritized feature list, testing the code thoroughly using unit, regression, and usability tests, and documenting everything.

Mark Wilkinson (DiRAC HPC Facility, UK) spoke next, presenting Research Software Engineering – the DiRAC facility experience. The science requirements for DiRAC demand a 10-40fold increase in computing power to stay competitive, and this increase cannot be delivered solely by hardware. Software vectorization and code efficiency is vital, and RSEs are increasingly important to help with, for example, code profiling, optimization, and porting. DiRAC’s three full-time RSEs are embedded in teams, their time allocated through a peer-review process. Wilkinson showed that the use of RSEs has paid off well for DiRAC, with, for one project, a factor 10 speed-up by optimizing a particular code.

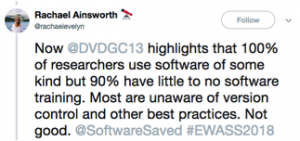

Mark Wilkinson (DiRAC HPC Facility, UK) spoke next, presenting Research Software Engineering – the DiRAC facility experience. The science requirements for DiRAC demand a 10-40fold increase in computing power to stay competitive, and this increase cannot be delivered solely by hardware. Software vectorization and code efficiency is vital, and RSEs are increasingly important to help with, for example, code profiling, optimization, and porting. DiRAC’s three full-time RSEs are embedded in teams, their time allocated through a peer-review process. Wilkinson showed that the use of RSEs has paid off well for DiRAC, with, for one project, a factor 10 speed-up by optimizing a particular code.  The focus on software engineering continued with a talk on Software Engineering Training for Researchers delivered by David Perez-Suarez (UCL, UK). He presented information he had gathered by conducting a quick survey to learn, among other things, what software development training researchers had gotten. His recommendations for training include running or attending training taught by The Carpentries, asking that training be conducted in conjunction with a large conference, such as the American Astronomical Society has been doing for several years, checking to see what software training might be offered by your university, creating your own study group, and co

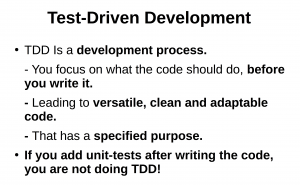

The focus on software engineering continued with a talk on Software Engineering Training for Researchers delivered by David Perez-Suarez (UCL, UK). He presented information he had gathered by conducting a quick survey to learn, among other things, what software development training researchers had gotten. His recommendations for training include running or attending training taught by The Carpentries, asking that training be conducted in conjunction with a large conference, such as the American Astronomical Society has been doing for several years, checking to see what software training might be offered by your university, creating your own study group, and co ntributing to an open source project. James Nightingale (DurhamU, UK) presented a very interesting talk on Test-driven Development in Astronomy. He convinced many in the room that using this technique for developing software will result in better software and less aggravation when coding. He stressed that test-driven development (TDD) is not a testing process, but a development process, and that the code coming out fully tested is a bonus. With TDD, the first task is not to write code, but to write a unit test and then run it to ensure it fails. Only after that do you write the code, and then test it. Through refactoring and testing code, you get instant feedback on whether the code’s functionality has changed, and code design becomes part of the development cycle.

ntributing to an open source project. James Nightingale (DurhamU, UK) presented a very interesting talk on Test-driven Development in Astronomy. He convinced many in the room that using this technique for developing software will result in better software and less aggravation when coding. He stressed that test-driven development (TDD) is not a testing process, but a development process, and that the code coming out fully tested is a bonus. With TDD, the first task is not to write code, but to write a unit test and then run it to ensure it fails. Only after that do you write the code, and then test it. Through refactoring and testing code, you get instant feedback on whether the code’s functionality has changed, and code design becomes part of the development cycle.

The session then moved on to software sustainability with Bruce Berriman’s (Caltech/IPAC-NExScI, US) talk on Sustaining The Montage Image Mosaic Engine Since 2002. Montage  has become increasingly robust and versatile over the years, is embedded in various archives and processing environments, and has been used in other disciplines as well as in astronomy. It has been cited more in information technology literature than in astronomy literature, though uptake of Montage was initially slow. Berriman made the point that design drives sustainability; all Montage releases inherit the design, and each module performs one task. He advocates listening to users and learning from their experiences, and shared his adage that “the grumpier the user, the more valuable the suggestions.”

has become increasingly robust and versatile over the years, is embedded in various archives and processing environments, and has been used in other disciplines as well as in astronomy. It has been cited more in information technology literature than in astronomy literature, though uptake of Montage was initially slow. Berriman made the point that design drives sustainability; all Montage releases inherit the design, and each module performs one task. He advocates listening to users and learning from their experiences, and shared his adage that “the grumpier the user, the more valuable the suggestions.”

The last two talks of this first session focused on Python, and covered the growing use of this language in astronomy, the reasons for this growth, the support that is available for the language, and information on one very popular package written in Python. Amruta Jaodand  (ASTRON, NL) presented A Walk Through Python Ecosystem, starting with its early development in 1989 by Guido van Rossum at the University of Amsterdam. The advantages of Python include simplicity and natural flow and an extensive, powerful standard library. Strengths of the language include the development of scientific, numerical, and statistical packages and its Python Package Index (PyPi), which enables module and package sharing. Jaodand shared some of the learning materials available for Python, including python4astronomers, and also a lovely Easter egg about Python that is too long to include here and is worth reading. One of the most important astronomy packages is AstroPy, and Jaodand’s talk was followed by The Astropy Project: A community Python library and ecosystem of astronomy packages, presented by Brigitta Sipocz (AstroPy, UK). AstroPy provides software for many common astronomy needs; in addition to the core library, there are many affiliated packages. All of these packages adhere to coding, testing and documentation standards that have been developed by the AstroPy coding community. Sipocz also discussed the community, with members of the team having one or more of its many roles. The number of collaborators continues to grow, and the community welcomes new members, and labels packages that are particularly friendly for a new contributor to work on.

(ASTRON, NL) presented A Walk Through Python Ecosystem, starting with its early development in 1989 by Guido van Rossum at the University of Amsterdam. The advantages of Python include simplicity and natural flow and an extensive, powerful standard library. Strengths of the language include the development of scientific, numerical, and statistical packages and its Python Package Index (PyPi), which enables module and package sharing. Jaodand shared some of the learning materials available for Python, including python4astronomers, and also a lovely Easter egg about Python that is too long to include here and is worth reading. One of the most important astronomy packages is AstroPy, and Jaodand’s talk was followed by The Astropy Project: A community Python library and ecosystem of astronomy packages, presented by Brigitta Sipocz (AstroPy, UK). AstroPy provides software for many common astronomy needs; in addition to the core library, there are many affiliated packages. All of these packages adhere to coding, testing and documentation standards that have been developed by the AstroPy coding community. Sipocz also discussed the community, with members of the team having one or more of its many roles. The number of collaborators continues to grow, and the community welcomes new members, and labels packages that are particularly friendly for a new contributor to work on.

Slides from this session

Software Engineers as Partners in Astronomy Software Development by John Wenskovitch (PDF)

Research Software Engineering – the DiRAC facility experience by Mark Wilkinson (pdf)

Sustaining The Montage Image Mosaic Engine Since 2002 by Bruce Berriman (pdf)

Software Engineering Training for Researchers by David Perez-Suarez (Google doc) | blog post

Test-driven Development in Astronomy by James Nightingale (pdf)

Pingback: Software in Astronomy Symposium Presentations, Part 2 – ASCL.net

Pingback: Software in Astronomy Symposium Presentations, Part 3 – ASCL.net

Pingback: Software in Astronomy Symposium Presentations, Part 4 – ASCL.net

Pingback: Software in Astronomy Symposium Presentations, Part 5 – ASCL.net

Pingback: Software in Astronomy Symposium Presentations, Part 6 – ASCL.net