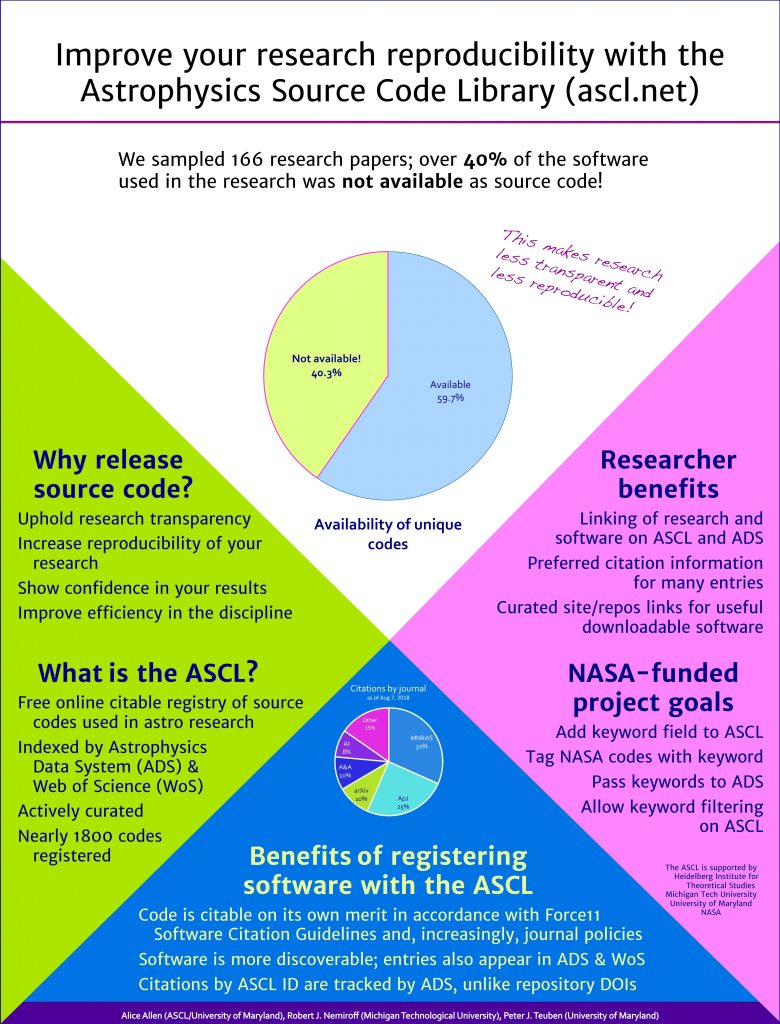

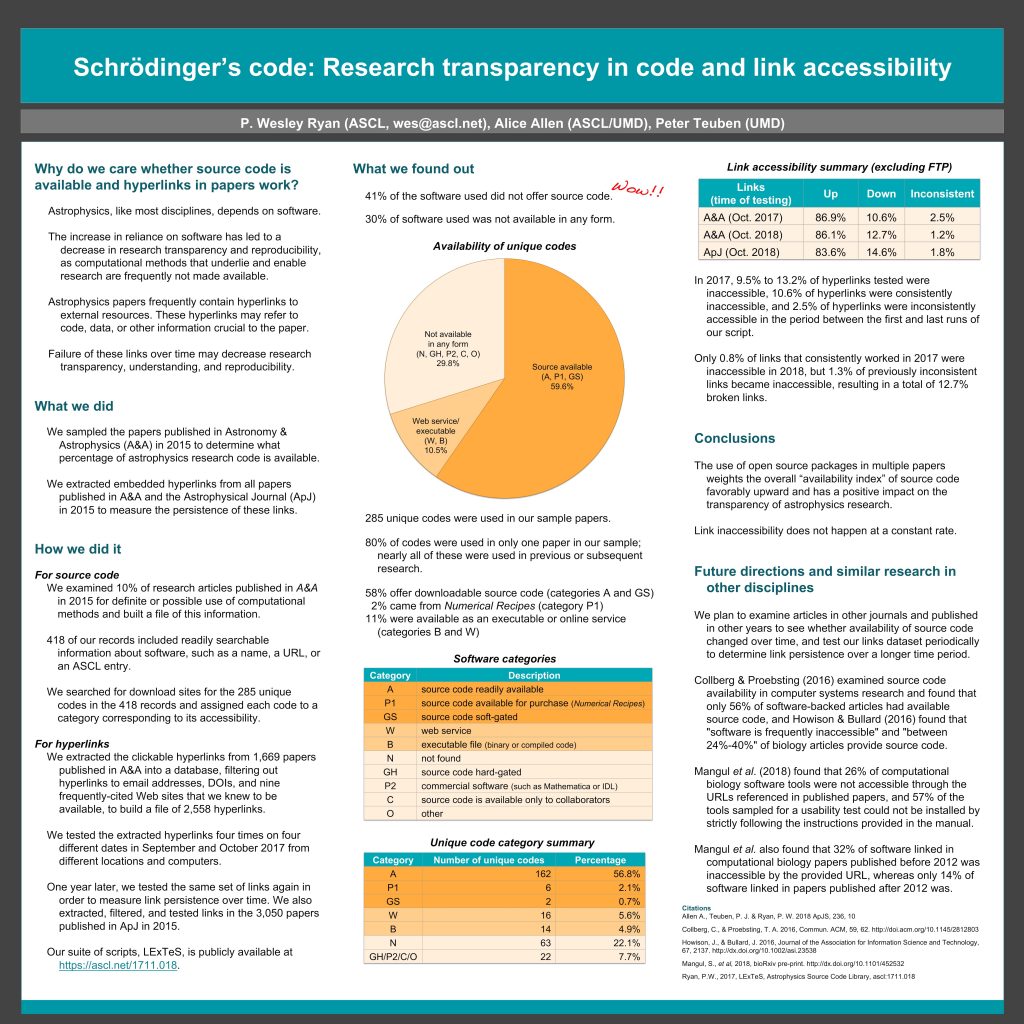

Astronomers use software for their research, but how many of the codes they use are available as source code? We examined a sample of 166 papers from 2015 for clearly identified software use, then searched for source code for the software packages mentioned in these research papers. We categorized the software to indicate whether source code is available for download and whether there are restrictions to accessing it, and if source code was not available, whether some other form of the software, such as a binary, was. Over 40% of the source code for the software used in our sample was not available for download. As URLs have often been used as proxy citations for software and data, we also extracted URLs from one journal’s 2015 research articles, removed those from certain long-term reliable domains, and tested the remainder to determine what percentage of these URLs were accessible in September and October, 2017. We repeated this test a year later to determine what percentage of these links were still accessible. This poster will present what we learned about software availability and URL accessibility in astronomy.

P. Wesley Ryan, Astrophysics Source Code Library

Alice Allen, Astrophysics Source Code Library/University of Maryland

Peter Teuben, University of Maryland