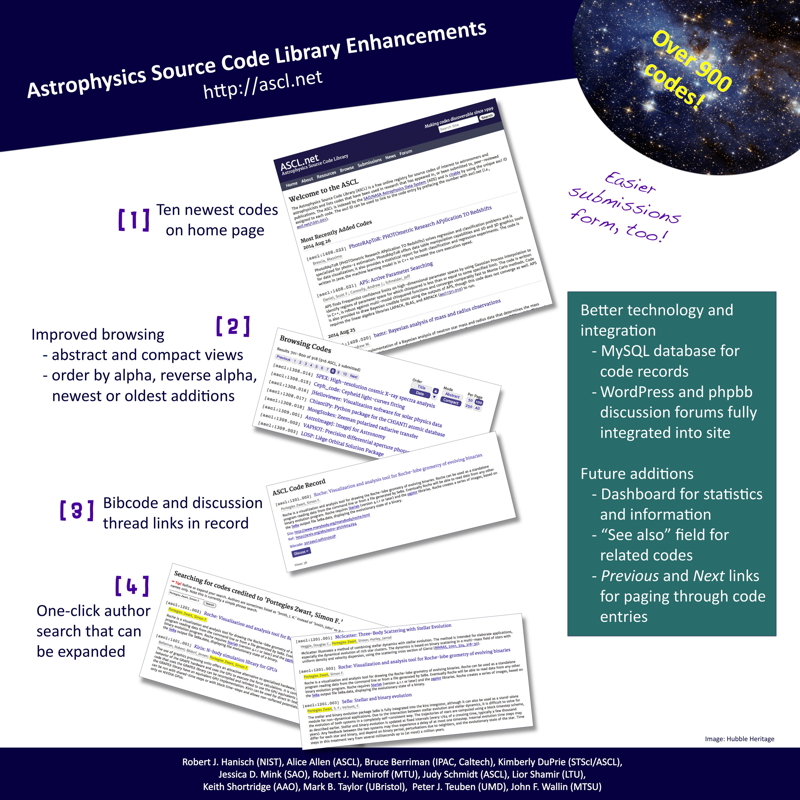

Abstract: The Astrophysics Source Code Library (ASCL) is a free online registry of codes used in astronomy research; it currently contains over 900 codes and is indexed by ADS. The ASCL has recently moved a new infrastructure into production. The new site provides a true database for the code entries and integrates the WordPress news and information pages and the discussion forum into one site. Previous capabilities are retained and permalinks to ascl.net continue to work. The site offers more functionality and flexibility than the previous site, is easier to maintain, and offers new possibilities for collaboration. This presentation covers these recent changes to the ASCL.

Authors: Robert Hanisch (National Institute of Standards and Technology)

Alice Allen (Astrophysics Source Code Library)

Bruce Berriman (Infrared Processing and Analysis Center, California Institute of Technology)

Kimberly Duprie (Space Telescope Science Institute)

Jessica Mink (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics)

Robert Nemiroff (Michigan Technological University)

Lior Shamir (Lawrence Technological University)

Keith Shortridge (Australian Astronomical Observatory)

Mark Taylor (University of Bristol)

Peter Teuben (University of Maryland)

John Wallin (Middle Tennessee State University)